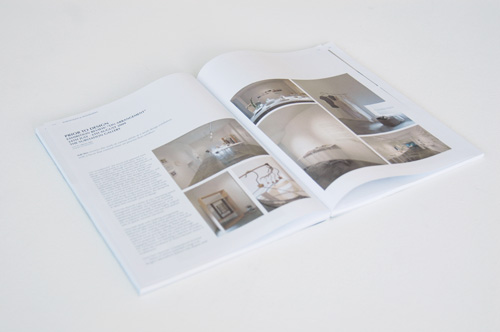

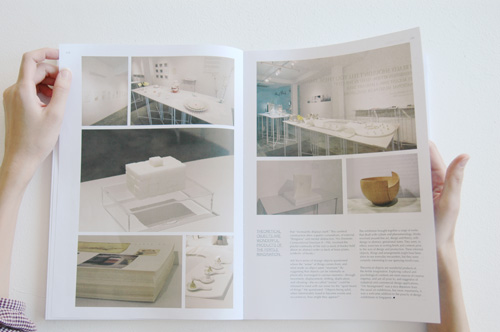

One could have easily mistaken the gallery for a showroom of household wares. That is the illusion created by the works at the exhibition, : on arrangement, at the Substation Gallery which ended its run on Thursday. The objects on display, ranging from clothes hangers, flower vases to dinnerware are as trite and quotidian as the notion of the “everyday” can possibly get, but the usually concomitant kitsch that comes with the “everyday” is absent.

That is perhaps the showroom effect. By lifting utilitarian objects out of the messiness of domestic life into the squeaky clean and slick premises of the contemporary art gallery, the image of a sanitised domestic utopia emerges. Shiny, clean utensils accompanied by flower pot embellishments at the side completes our fantasy of the the perfect dining room.

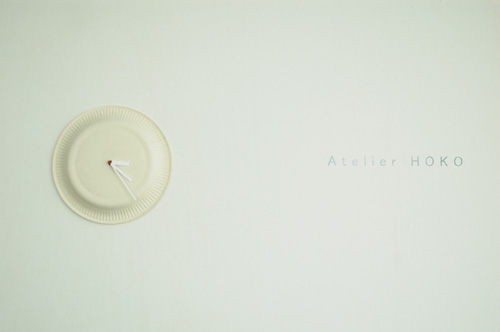

This image of a showroom is but a deceiving first impression, for in a showroom, we are disinterested spectators passively enjoying the pretty showcase. But through Atelier HOKO’s act of arranging these objects as art pieces in a gallery, the exhibition moves beyond being a mere showroom to being a thoughtful examination on the nature of arrangement, and by extension the power dynamics between the arranger and the arranged. And it is also in this new context of an art exhibition that we begin to reconsider the aesthetics of the utilitarian in a different light – almost a paradoxical notion in itself as the aesthetic and utilitarian are diametric opposites.

Atelier HOKO’s The Plinth’s small scale and minimalist design almost understates the profound message on arrangement that is brought forth. It shatters the notion of arrangement as the banal activity of physical adjustment, highlighting the power of recontextualisation the arranger wields in his act of arrangement, whether it is done consciously or not. The Plinth points directly at an institution that has become almost singularly about arrangements, rearrangements and repositionings, where the act of moving an object from one place to another has become the key mechanism for creating purpose and value. And this institution is none other than art itself. The act of placing an object on a plinth requires almost the same physical demands as any table arrangement activity, but the authorial power the former holds is immense.

Domestic Compositional Structure I (Shelf of Shelves) and Domestic Compositional Structure II (Pile) (2009), by Hans Tan

Multiple organisational structures are represented in Hans Tan’s Domestic Compositional Structure I (Shelf of Shelves). Each empty shelf displays a shelf of a diminished scale, creating shelves within shelves. A shelf is often seen as an organisational unit and hardly as an independent object on its own. In Tan’s repeated diminishing shelves, however, we see the shelves claiming a space for their own, asserting their unexpected ability not only to organise, but also to be organised and arranged. The adjacent accompanying work Domestic Compositional Structure II (Pile) is less conceptually layered. After all, it is difficult to be in any way inspired by a stack of books. The fundamental idea in the work is the impulse to stack, which is apparently one of the most elementary instincts that constitutes arrangement. But surely more could have been done to achieve a more nuanced and original interpretation.

An extension of the notion of arrangement is that of rearrangement. In rearranging, we reconfigure existing arrangements that are already there, either by nature, by coincidence or a prior decision. In rearranging, we frame new conditions that were previously unperceived. This act of framing is crucial to the exhibition’s attempt at rehabilitating the utilitarian and quotidian as aesthetically and formalistically rich.

Takeshi Kuboi’s and Naoko Kubo’s Stationery-Ware performs such a framing by the defamiliarising stationery and tableware via their hybrid amalgamations. Both tableware and stationery are similar in the way we regard them only in terms of their instrumental value, as a mere tool for the satisfaction of either our gustatory or creative needs. By creating these hybrid forms, the artists sensitise us to the inherent properties of both stationery and tableware and thus compel us to regard them for what they are. This transition from the realm of the utilitarian to the plinth of the aesthetic is essentially a conferral of identity and autonomy, achieved by the seemingly simple act of rearrangement.

Arrangement can also be seen as a form of social codification, as illustrated by a set of photographs of the interiors of a Harari residence in Ethiopia, which walls are entirely filled with decorative baskets. The arrangement of the baskets follows a strict code where each kind of basket has a particular place. This schematic mode of arrangement is assured by the mistress of the house. Each different arrangement thus takes on a different value and significance, expanding the notion of arrangement in this case into a kind of social language. Notably, the explanatory notes of the work also explore the utilitarian and aesthetic divide in the form of the physical placement of the basket. While the insides of the basket serves an obvious functional value, such a function becomes hidden when the basket is displayed on the wall. It is its exterior that is visible which enables the basket to assume an immediate aesthetic value that overwrites its utilitarian origins. By physical arrangements and repositionings, new values and meanings are created.

Meanwhile, Ash Y. S. Yeo’s On Hyperfunction: Dysfunctional Objects and Aboutness of Things, and Arrangements, critically examines the subject-object dichotomy. Yeo’s objects are distorted and enigmatic versions of their everyday counterparts. Wooden bowls are “sliced” into two pieces while other tableware are distorted into amorphous forms and encased in glass containers. The ideas detailed in the accompanying captions are rich and profound, but the works speak too little by themselves to articulate these ideas in their totality. The distortion of form seems to be Yeo’s attempt at creating narrative potential in the objects, as a part of a larger attempt at redefining the objects as subjects with their own individual personality. Apparently, he also seems to be encouraging the viewer to look beyond the “thingness” of objects to consider their “aboutness”, or in other words, to consider them not as physical matter, but as sites of transient occurrences and arrangements. There is an implicit suggestion that the line between “thing” and “event” is indistinct. However, the minimalist design and deadpan impersonality of the pieces leaves the audience too distanced and cold to contemplate such ideas in detail.

In comparison, Yeo’s About Anomalies and Paranormalies is the more effective piece among the artist’s works in the gallery. An exploration of the nature of reality, the work features a mirror dissecting a flower vase into two halves, yet retaining a “complete” image of the flower vase with the presence of the mirror image as a substitute for the hidden half. The mirror here is the magical surface where the real disappears into its virtual counterpart. It exists as the very fringe of our objective reality. It completes the object by melding the real and the virtual, creating an object that is in a sense, a “paranormaly”.

At the other end of the gallery are the new media works, which include a series of video projections. Collectively, the videos reflects the need to arrange as a basic, visceral human impulse, screening footage of arrangement in our everyday lives. While most of the exhibited objects make appearances in the videos, the videos are not mere recorders as the time-based element of video is at times manipulated to create new phenomenological realities. The sequence of still images in Atelier HOKO’s Vessels for instance results in what appears like a frame-by-frame animation of the objects, creating an interaction between the static quality of the stills and the time-based nature of the work. This interaction is a reflection of the fluidity that exists in the transition between “thingness” and occurrences.

The Word ‘Thing’, also by HOKO distinguishes itself among the video works with its playful and cheekily direct interpretation of the notion of arrangement. The video essentially shows the hand of an individual arranging and rearranging the individual letters that form the word “thing”. Here, HOKO effectively literalises the notion of “arranging to create new meaning and value”, playing with both space and language.

Another new media work, Yong Jieyu’s Arranged Quotes, features the taglines written by his friends on his MSN instant messenger friends list that are projected on a computer screen. A software mines the taglines written by his friends every ten minutes and rearranges them in the display format of how famous people would be quoted. Here, by appropriating a particular textual convention associated with the wise and quote-worthy, Yong is evidently exploring the power that textual arrangements can have upon the perceived significance of the words. Unfortunately (or fortunately), Yong’s little experiment seems to lead to little exciting new discoveries. Many of the quoted taglines remained as they were, as the unimportant musings of people utterly irrelevant to our lives.

To describe the exhibition as a series of visual understatements is not entirely a pejorative statement, for it could only mean that it is an accurate reflection of our regard of the word “arrangement”. The act of arrangement is so integral to our everyday lives that it goes largely unnoticed and ignored. The minimalist design of the pieces best succeeds in drawing us to the beautiful simplicity of arranging that is however embedded with profound meaning and value, which can only be uncovered through thoughtful introspection. But simplicity does come with its risks for at times the work simply says too little. As a result, some of the pieces merely remained as pretty objects to look, instead of being thoughtful arrangements to be reflected upon.

: on arrangement was on display at the Substation Gallery from 21 July to 6 August 2009.

12.30.09

12.30.09